IADS Exclusive: 2021 IADS Academy - Omni-cluster for omnichannel

In early 2021, the IADS Academy participants were set the task by their CEOs of suggesting ways to develop a truly omnichannel P&L and related KPIs relevant to department stores. Their proposals covered several areas including KPIs and data sharing (see Presentation to CEOs at IADS General Assembly, 28 October 2021; and IADS Academy 2021 report). One of the proposals called for the development of “omni-clusters” of customers. The IADS has attempted to develop this idea.

Imitate or innovate?

In the early days, many omnichannel department stores in effect created a separate and competing business within their companies: e-commerce, which started as an “add-on”, often an experiment, was operated on the same principles as the traditional stores, with the differences that selling took place on a website rather than in physical stores, and that customers were delivered at home instead of carrying their purchases away with them.

As e-commerce began to include more merchandise categories, department stores saw the format as competition, just as they had seen big-box and discount retailers, then fast-fashion companies enter their market and address their customers. It was supposed that by getting involved in e-commerce, the danger could be fended off and those customers tempted by pure online retailers could be brought back to the fold. However, online retail proved to be bigger than expected, customers integrated it quickly into their retail habits and department stores found themselves running to keep up with the trend. Today, it is more of a scramble to adapt to the pandemic new normal. The puzzle of profitability of e-commerce was not solved, even by the pure players.

Integration into the traditional business has been unfortunately very expensive. The original business was not adapted and e-commerce was generally loss-making. Department store companies have had to operate simultaneously two business models: one in which the main cost centres have been real estate and people, as well as the new one requiring significant investment in systems, fulfilment and marketing. In spite of efforts to the contrary, the traditional department stores found themselves competing not only against new online companies but also being cannibalised by their own creation, at first a modest separate pilot but which soon grew into a Frankenstein monster. The admittedly complex model of the traditional department store was clearly inadequate for the job of operating online, and a fortiori inappropriate for an omnichannel retail operation. One consequence is that, under pressure from activist shareholder groups, some US companies have already or are considering spinning off the high growth dot.com part of the business to increase market valuation such as Saks Fifth Avenue and Hudson’s Bay, and also illustrated by the speculations on Macy’s, even if this approach sparks controversies. This suggests that they believe there is no answer to the omnichannel conundrum.

Struggling with channel conflict

Part of the problem has been, of course a shift in customer behaviour and expectations. It is clear that any business model which does not start from the customer is doomed to failure in what has been called “the age of the customer” (from say 2010). Starting from the belief that online customers were different from store customers, department stores operated two separate channels and only slowly came to the realisation that there was such a thing as an “omnichannel customer” (with higher spending than the single channel customer they had been dealing with).

But then the challenge of merging two business models with very different cost structures became apparent. Against the traditional conversion ratios of 40% plus, the online part of the business was confronted with rates as low as 1%-2%; against sales per square metre, online invoked profit per transaction; against shareholder expectations of bottom-line profit, online was operating as a start-up expecting no profit for at least 5 years but demanding rapid growth during that time; against B2B logistics based on store deliveries, online required quick and efficient B2C fulfilment.

As long as the online part of the business represented 5% or less of the total, then it was monitored separately in order to determine its profitability, return on investment and its longer-term future. As time passed, it became clear not only that online was here to stay, but also that it was contributing to store-based business (and vice versa) in a complex and organic way making it almost impossible to isolate online P&L from store-based P&L. (See for example how Macy’s is claiming to “scale omnichannel thinking across the entire customer journey”.)

The question then becomes how to determine the profitability of various parts of the business, how to attribute costs and sales. Furthermore, it has become clear also that the “best” customers are “omnichannel” customers, making full use of all the opportunities available to them across channels to search, gather information, purchase, pay, get delivered and return merchandise. However, it remains unclear to what extent they are the most profitable, as they “consume” expensive services which are implemented through expensive platforms.

Omnichannel means integration

And yet… many department stores are locked into the double P&L model and struggling to determine how to attribute sales and costs. Partly because so many employees are assessed on a series of inappropriate KPIs which actually discourage an omnichannel approach. And partly because data is unavailable to track customers, inventory, fulfilment, returns etc. in sufficiently granular form to allow appropriate attributions.

Integration of channels means first and foremost the integration of data allowing all channels to be under the same control and distribution system. For example, all data on any particular customer must be available in one accessible place whether it concerns purchases or returns in all channels, preferences, hard data as well as unstructured data.

Similarly, inventory data should be updated in real time, any priorities for particular channels need to be clearly set out in order that channel conflict does not develop from limited inventory.

At the same time, traditional KPIs which have been focussed on transactional records are no longer able to evaluate the sometimes complex drivers of customer decisions. It has been suggested that omnichannel KPIs should fall into four main categories: awareness, engagement, conversion, and loyalty. Thus, such KPIs might cover traffic and visits, recommendations and conversion rates, cross-channel conversion and baskets, and advocacy, lifetime customer value, revisit rate and frequency, for example. (See KPI suggestions.)

A new idea: “omni-cluster”

Since the customer journey has become omnichannel, it has arguably become necessary to use management tools and financial statements which reflect this development rather than struggling to attribute revenues and costs to different channels. The notion of “omnicluster” is a proposal in this direction.

Clustering in itself is not a new idea for department stores. Different clusters as applied to department stores include clustering by store capacity (space for example); by attribute (traffic, location, income profiles…); by sales (revenue, inventory turn…); productivity (revenue or gross margin per square metre); price (price profile, elasticity); multi-dimensional clustering; and more.

In the same way, customer clustering is also common. Using algorithms and AI it is generally defined as an improvement on rule-based segmentation since it allows clustering over many more dimensions; allows only small variance within each group; and can be made dynamic and reflecting the current state of data.

The proposal made by the IADS Academy was to bring the two ideas together to create customer clusters who shopped at stores, online, or both. This would potentially avoid the difficulty of separate or overlapping P&Ls for stores and online. The only rule is that any customer can belong to only one omni-cluster even if they occasionally shop, return, or collect in several physical stores. All revenues, returns and costs associated with a customer would belong to that omni-cluster.

It has been often remarked that not only does online bring customers to stores (and vice versa), but most online customers are more dense around an existing store (while this was a surprising discovery in the early days of omnichannel, it is now fairly obvious since most customers now shop online and stores are situated in the most important markets). In this case, it is clear that an omni-cluster may consist of one or more stores and the online customers residing around that store. This is the simple omni-cluster model as favoured by Magasin du Nord for example.

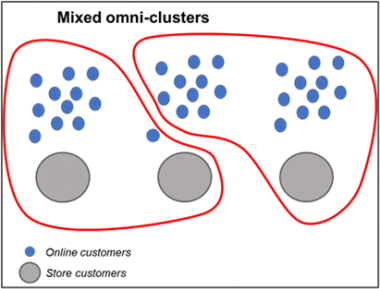

If, however, a number of online or omni customers have a preference for direct contact with a distant store (say a flagship store, or a store closer to their office rather than their residence), then one mixed omni-cluster might include a store, its geographically close online customers as well as online customers geographically closer to a different store. This may happen also if the stores are clustered by size as they are at Manor, for example.

If store customers are very mixed (tourists and locals, for example), then one can imagine an omni-cluster made up of local store customers plus online, and another partial omni-cluster made up of tourists and the much smaller online tourist customers. A business which involves franchised stores might include its own stores and all online customers in its omni-clusters but not include the franchised stores. These cases may be more appropriate at, say, Galeries Lafayette.

A series of ecosystems

As these examples show, the criteria for omni-cluster membership may obviously vary from one company to another according to its history, its organisation, its market etc. It is a flexible model. The definition criteria of omni-cluster will be a function of the particular circumstances of each company and its history as well as of the omnichannel strategy pursued by a company (aggressive online growth, new store openings or potential store closures etc.).

The aim is primarily to group revenues and costs into a number of omnichannel P&Ls which cover total operations of a cluster which can serve to manage operations (through the related KPIs), and which can be consolidated into a total business P&L. While the different omni-clusters can be compared, it is clear that none will be exactly comparable to any other. For example, geographical location or the number of stores in a cluster may have an impact on fulfilment costs.

However, the advantage of this model is that it highlights the profitability of the customers in any one cluster (for example how much they spend in all channels, frequency, rates of return, margin per customer etc.). Clearly the costs of store personnel also do not relate only to store customers, which distorts store-only P&Ls. Potentially it also allows the evaluation of the true loss of revenue through a store closure.

The kind of integration referred to above moves closer to an “ecosystem” perspective of the retail business. Indeed, a degree of “unbundling” will be necessary to evaluate the costs attributable to an omni-cluster. When that exercise is pursued, then it becomes possible to find potentially more appropriate, more efficient or more effective solutions before rebundling these into an omni-cluster ecosystem.

Warnings, dangers and the way forward

However, such a move would make it quasi-impossible to spin off the dot.com part of the business as has been done recently by HBC with Saks Fifth Avenue and Saks.com. There are currently some reports of Macy’s considering a similar move. It is clear, however, that these examples are financially motivated and a result of pressure from activist shareholders. They are also more appropriate to larger companies. A smaller omnichannel department store following the integrated omnichannel route will be capitalising on its unique status as what Bain has called a “regional gem”. Once established, an ecosystem can no longer be dismantled and split up into its original component parts. It competes as a whole, not as a multi-channel entity. However, this commitment is no more risky than the spin-off of the dot.com part of the business may turn out to be for larger companies which choose this way.

The omnichannel route might also imply considerable reorganisation of the traditional bricks and mortar assets as illustrated by the John Lewis case which is closing and shrinking so many of the stores it (perhaps unwisely) opened while it was expanding its online business (now around 60% of total revenue). It also sold its Ocado stake in 2010 for £250m which would be worth nearly £2bn today. Rather than spin off the online business, it is reshaping the total business under a new team, focusing on own brands, convenience, high productivity, sustainability, and the integration of formats.

John Lewis raises the question of how to implement the shift towards real omnichannel in today’s retail landscape. Clustering, new KPIs and rejigged P&Ls cannot be put in place in a day. The question therefore is: What would a transition phase towards omni-cluster P&L look like? Who should guide the transition, and how can investors be won over to support this longer-term shift?

Credits: IADS (Dr. Christopher Knee)